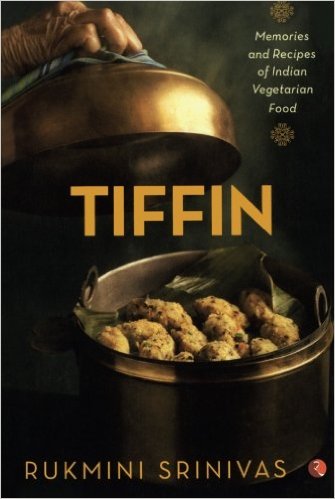

Book Review: Tiffin By Rukmini Srinivas

P Srinivasan reviews Tiffin by Rukmini Srinivas, a food memoir and finds it a rich tapestry of vegetarian food and of the times gone by.

This is an eminently readable book. It is unique in that it is two books, one of recipes and another of reminiscences, combined into one. The author, Rukmini, (‘Rukka’ to her close friends) is the wife of the eminent sociologist Dr. MN Srinivas. She holds a Master’s Degree in Geography and has taught in Queen Mary’s College, Madras, as it then was, and later in the Delhi School of Economics. She has travelled extensively in India and abroad. In an interesting introduction, she traces the etymology of ‘tiffin’ from an eighteenth century English slang ‘tiffing’ for ‘sipping’ or ‘eating out or drinking out of mealtime.’ The use of the word is now virtually confined to the South Indian states where it has gained wide currency and is well understood.

As the title of the book suggests, what stands out is Rukmini’s passion for cooking and experimenting with new recipes of vegetarian food all the time. Even as a schoolgirl she watched with keen interest, lending a helping hand, while her uncle, ‘Dr Chittappa’ (Dr Natesan), a doctor-turned-cook in his wife’s absence, made masala vadai. Her father, Naganathan, who served in the Military Accounts department in pre-independent India, could cook too. She describes how he once made vegetable cutlets like a professional. Her mother too was an excellent cook. Cooking was therefore, in her genes. Even now at 88, in Boston where she stays with her daughters, she continues to cook at home. She also hosts a local TV show there on Indian vegetarian cooking.

Rukmini was in the habit of sending her daughters living in the United States “easy” recipes of snacks to make at home. While drawing on her memory for this, she “recalled the many anecdotes and narratives about the people and places associated with these recipes,” which she passed on to them along with the recipes. Happy to read the anecdotes, the daughters urged her “to share them with a wider audience.” That is how this book was born, weaving the anecdotes into the recipes in such a way that every set of recipes is preceded by an anecdote in which a reference to the dish or dishes in question occurs in some way or the other. These “vignettes from my life seen through the prism of tiffin” written in a free-flowing style make pleasant reading.

The anecdotes are not in any chronological or logical order and not exhaustive to constitute an autobiography. Yet a broad picture emerges of her life of 88 years. Third of nine siblings, she was born in Bangalore in 1927, where her father was posted at the time. She attended convent schools in different cities in the country where his career took them. While she cherishes her stay in Poona and the schools she attended there, she found school life in Madras restrictive. In Poona, she could wear knee-length skirts, double plait her hair, ride a bicycle round town, and talk freely with boys, all of which met with tacit disapproval in Madras.

Memories Served Through The Years

Joining Queen Mary’s College in 1946, she found the hostel food “unappetising.” However an agreeable choice was available in a mobile canteen “parked right opposite the college every evening” and she became its “ardent devotee.” Love of good food, her constant theme right through the book, naturally led to a keen interest in cooking.

Completing her Masters in Human Geography from Queen Mary’s College in 1952, Rukka was appointed as a Lecturer in the same college. She was nominated Secretary of the Dramatic Association and allotted a room in the staff quarters. It was here in August 1955 that Dr MN Srinivas or ‘Chamu’ as she refers to him, called on her. Only a couple of days earlier she had been informed of Chamu’s impending visit by his Bengali colleague, Sankho, who had met her accidentally in Tanjore in 1953. “Although a pipe-smoking brown Englishman from Oxford”, Sankho wrote, “he (Chamu) is an interesting person.” After an extended tete-a-tete over two days, they decided to get married. Chamu, a Shrivaishnava from Mysore and Rukka, an Iyer from Tanjore, tied the knot on November 21 in a simple Hindu ceremony in front of close relatives.

Chamu was Professor of Social Anthropology in Baroda University. Rukka joined him in Baroda where she had occasion to demonstrate South Indian cuisine and exchange notes on cooking with a Gujarati couple, the Amins. A year later, in 1956, Chamu and Rukka left for the US, to Berkeley. They travelled by ship. She was seasick and disliked the food served on board. On reaching New York she enjoyed delicious South Indian food in an Indian restaurant. Happy to have her own kitchen in Berkeley, she became “immersed in being a spouse and in running a home, experimenting with cooking…”

Not wanting to use the pots and pans in the house in which non-vegetarian food had been cooked, she bought some essential kitchenware. She introduced her American neighbours to Indian delicacies.

The famous writer RK Narayan, a family friend of Chamu’s who was also in Berkeley at the time, was a frequent and welcome visitor. Averse to using an electric blender to grind fresh spice powders, she borrowed a flat stone grinder from the Anthropology department museum. She adds that “nowadays in Boston also” she uses a granite mortar and pestle. “My daughters”, she quips, “are still hopeful that I’ll start using the food processor some day.” Another interesting revelation is that in spite of her long stay in the US she has “not succumbed to the ‘ease’ of wearing western clothes,” continuing to “shuffle in my saree even during the deep winter in Boston.”

From Berkeley, Chamu moved to Delhi in 1958 to start the Department of Anthropology in Delhi School of Economics. In 1964, he was invited to the Centre for Advanced Studies in the Behavioral Sciences in California for a year. This time they travelled by air. She was the mother of two girls by then. Stopping at Rome briefly en route, she was thrilled to have an audience with the Pope. However, she says, “it was an extended period of fasting for me” since all preparations contained either egg or meat. In her new home in Menlo Park, California, her strict vegetarianism became a hot topic of conversation. She sent vegetarian recipes to a local magazine and started classes in Indian vegetarian cooking. During their next one-year stint in the same place in 1970, she continued to hold classes, but this time, informally and not on a regular schedule.

In 1972, Rukka and family relocated in Bangalore where Chamu joined Dr VKRV Rao’s Institute of Social and Economic Change, Rukka adding a few more recipes to her repertoire. Chamu passed away in Bangalore in November 1999. Since February 2000, the author spends most of her time with her daughters in Boston.

Pick Of The Best

Rukka being a strict vegetarian who eschews even eggs, the recipes in the book are all vegetarian. Since she has travelled widely, they are from many parts of India. Bearing in mind foreign readers, she has, in most cases, given the name of the nearest English equivalent of the dish in question. The exhaustive list of ingredients set out in every recipe and the step-by-step method of processing them should embolden even a novice to try it out. There are over a hundred recipes. Some, picked up at random to illustrate the care with which they have been drawn and their geographical spread, are listed below:

Masala Vadai: A South Indian favourite, which she describes as “aromatic, crisp and spicy lentil fritters, the Indian falafel.” “Serve hot or at room temperature,” she advises. This is followed by a recipe for a chutney to go with it.

Vegetable cutlets: “Serve hot with orange rind-green chilli relish” is her useful tip. How to make the relish is the next recipe.

Garam masala: Mainly a North Indian preparation used as an essential spicy ingredient in vegetarian and, for that matter, non-vegetarian dishes too.

Potato Bhaaji: A street food in Pune to go with puri which, she suggests, can go well with the South Indian dosai as well.

Delhi-style Pea samosas: These are now made and sold all over the country. She learnt this recipe from a Delhi based friend of her mother’s. As with other main dishes, she is careful to add a recipe of a tasty add-on to the main dish, ‘raisin-tamarind chutney’ in this case.

Idada: Better known as ‘dhokla,’ the Gujarati cousin of the South Indian ‘idli’ is a welcome recipe for the health-conscious who would avoid fried food. While grinding the batter in a blender, she advises in her characteristic attention to detail, ‘occasionally stop the blender to push down the batter from the sides with a spatula, and start grinding again… Cut into 1-inch squares and transfer to a serving dish.’ This is followed by an add-on that is usually served with it, the ‘coconut tomato chutney.’

Delicious parantha, the thought of which makes the mouth water, best made by housewives in Uttar Pradesh, can now be replicated at home anywhere by the readers of this book. Thayir vadai, ulundu vadai, masala dosai, ragi dosai, multigrain dosai, vegetable bajji, vermicelli upma, khara obbattu, akki roti, Rajasthani mathri are some other savoury items.

Turning to the sweet dishes, you have banana halwa, appam, sojji appam, pori urundai, sweet potato polees, shahi tukda which she introduces as a Hyderabad sweet, Rabadi (basundi), Gaajar halwa, Badam Halwa and jalebi. These lists are by no means exhaustive.

The lively account of the author’s relatives and friends is well backed up by family photographs from her album even though some have acquired a sepia hue with age. The recipes, as pointed out in the blurb, “are accompanied by evocative photographs.” The scenes described by the author are illustrated by realistic drawings. The depiction of three farmers driving in their bullock carts laden with their produce to the Santhe in Tanjore (p.183), the scene inside Palani’s Bakery (p.159) and the temple in Rameswaram (p.315) are striking, adding to the flavour of the book.

We invite senior citizens to share their writings, short stories, poems and reviews with us. Please send us an email at connect@silvertalkies.com.

Feature Image Courtesy: Pixabay

Comments

Post a comment